Mathematical Poetry, Poetic Mathematics . . . dots and lines and links

by JoAnne Growney

Once a professor of mathematics at

1. Poems with Mathematical Imagery

Figures of Thought by Howard Nemerov

Significant Landscape (VI) by Wallace Stevens

The Mouse's Tale/Tail by Lewis Carroll

An early square poem by Henry Lok

Small square poems and The Bear Cave

Can we HEAR the SHAPE of a poem?

Syllabic Verse: Haiku by Basho;

The Icosasphere by Marianne Moore

3.1 Sources and links to poems with mathematical imagery sampled above (and others)

3.2 Sources and links for visual or concrete poetry

3.3 Extras:

3.3.1 Counting Rhyme Schemes: Catalan and

3.3.2 Mathematical Love Poetry and Poetry organized by the Fibonacci numbers

1. Poems with Mathematical Imagery

As mathematicians smile with delight at an elegant proof, others may be enchanted by the grace of a poem. An idea or an image expressed in just the right language--so that it could not be said better--is a treasure to which readers return. Particularly thrilling for me is to read a work from a poet who is fluent in the language of mathematics and uses mathematical images to make a poem vivid. I begin with a few of my favorites.

Rita Dove served as poet-laureate of the

Geometry by Rita Dove

I prove a theorem and the house expands:

the windows jerk free to hover near the ceiling,

the ceiling floats away with a sigh.

. . .

(Copyright considerations have kept me from quoting Dove's poem and certain other poems in their entirety; Section 3.1, below, supplies print-sources for this and other poems. Additionally, extensive information about all poets mentioned herein can be obtained online using Mozilla Firefox or Google or another search engine.)

Return to Outline Top of page

Poet Laureate of the

Figures of Thought by Howard Nemerov

To lay the logarithmic spiral on

Sea-shell and leaf alike, and see it fit,

To watch the same idea work itself out

In the fighter pilot's steepening, tightening turn

Onto his target, setting up the kill,

And in the flight of certain wall-eyed bugs . . .

Born in

from Six Significant Landscapes (VI) by Wallace Stevens

Rationalists, wearing square hats,

Think, in square rooms,

Looking at the floor,

Looking at the ceiling.

They confine themselves

To right-angled triangles.

If they tried rhomboids,

cones, waving lines, ellipses--

As, for example, the ellipse of the half-moon--

Rationalists would wear sombreros.

Return to Outline Top of page

Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1996, Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska (1923- ) is skilled at using specific details with wit and irony and offering new insights, often moral in nature. Extremely popular in her native

Pi by Wislawa Szymborska TR . Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh

The admirable number pi:

three point one four one.

All the following digits are also initial,

five nine two because it never ends.

It can't be comprehended six five three five at a glance.

eight nine by calculation,

seven nine or imagination,

not even three two three eight by wit, that is, by comparison

four six to anything else

two six four three in the world.

The longest snake on earth calls it quits at about forty feet. . . .

A challenge that any word-lover may enjoy is to create a 26-word poem whose words begin with succeeding letters of the alphabet. Here is an "analytic geometry" poem I wrote in response to that challenge. (Reader, you might try it too. Beyond mathematical topics, there are many themes with varied vocabularies that yield interesting results: for example, food or gardening--either flower or vegetable--or travel or bird-watching or a visit to the zoo.)

Axes beget coordinates,

dutifully expressing

functions, graphs,

helpful in justifications,

keeping legendary mathematics

new or peculiarly quite rational

so that understanding's visual

with x, y, z.

Return to Outline Top of page

2. The Shape of a Poem

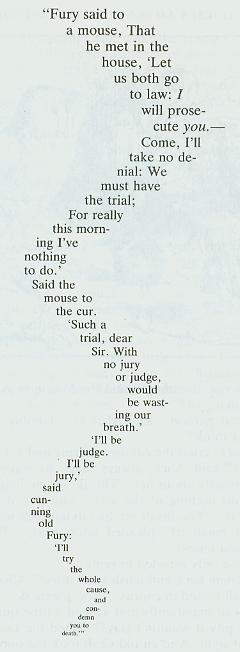

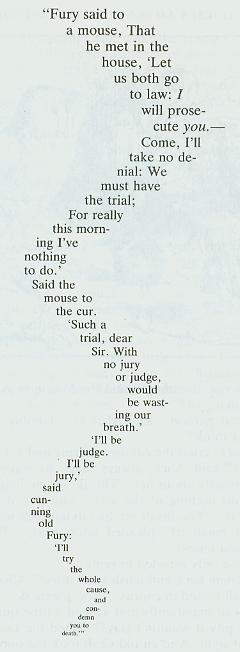

One evident connection between mathematics and poetry is that of counting--poems have a chosen number of stanzas, stanzas have a number of lines, lines have a number of syllables. Beyond that, there is the shape of a poem. Often it is more-or-less a rectangle; sometimes the shape is not at all rectangular. For example, In Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll tells a tale of a mouse’s tail using a long-tail-shaped arrangement of words. Such a poem--which is offered in the shape of its subject--is called a concrete poem. A more general category is visual poetry--in which the shape of the poem in some general way relates to the meaning of the poem.

"Mine is a long and a sad tale!" said the Mouse, turning to

"It is a long tail, certainly," said

Return to Outline Top of page

My stanza, "More than Counting," offered below, is a type of visual poem; its layout and content are related. This stanza also shows the sound-effect of different line lengths. If you read it aloud, you may notice how your pace changes as the length of line changes and you "feel" the shape of the poem.

One

added

forever

joined by zero,

paired to opposites--

these build the integers,

base for construction of more

new numbers from old : ratios,

radical roots and transcendentals,

transfinite cardinal--constructions bold!

Return to Outline Top of page

To more carefully understand effects of line length on the way we hear a poem, consider these next two stanzas; in the first, each line contains only two syllables. (This works best if you read them aloud.)

Short lines

like this

create

poems

through which

we move

slowly

giving

weight to

each word.

BUT, even WITH a much LONGer LINE,

my READer will READ it ALL in one BREATH—

this will SPEED the EYES aLONG the LINE

to REACH the END before the CHANCE to forGET.

For poets as with musicians and mathematicians there is a sub- or semi-conscious inner ear that hears and keeps track of properties such as the number, the quality, and the duration of the sounds in a poem. In the four-line stanza just above, the bold-uppercase syllables designate accented or stressed syllables and there are four of them in each line. Poetry in which accents are counted is called accentual verse; if syllables are counted in each line we have syllabic verse. Poems written in English are more likely to be accentual that syllabic, but the traditional Japanese forms such as Haiku count syllables and much of the poetry written in Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish) is syllabic rather than accentual.

Although there need not be an underlying pattern for a poem, in those works that please the ear it is likely that some pattern exists. Still, just as we do not need to know the key of a musical composition to enjoy it, similar ignorance is acceptable with poetry. We will go on to explore a few square poems (in which the number of lines and the number of syllables per line are the same) and briefly consider other syllabic patterns.

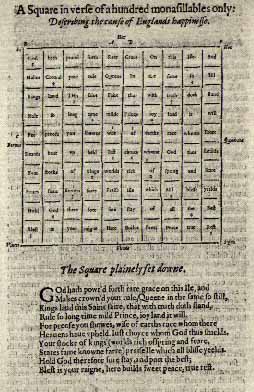

An early example of a square poem is the one just below, "A square in verse of a hundred monasillbles only: Describing the sense of

Just as constraints of continuity or differentiability or preservation of distance limit the choices of functions available in a particular mathematical situation, so constraints of form or shape in a poem direct the poet toward some words while eliminating others. For example, we cannot satisfy the form of "More than Counting" by starting with "number" or "develop" or any word with more than one syllable.

Mathematicians enjoy pushing against constraints to find what is possible despite their presence; I enjoy a similar struggle in poetry. For example, when I wanted to write about my decision to be polite even though somewhere inside I feel very uncivil, the constraints of a 3 x 3 square poem led me to:

serve as well

as true ones.

Or, remembering that my mother used to advise me when my left eye teared with pain from a grain of sand blown into it, rub your right eye really hard and that will help--the shape of a 4 x 4 square led to:

When lovers leave,

avoid laments.

Grab a cactus—

new pain forgets.

Here are other squares:

When browbeating fails— More than the rapist, fear

gaudy, hazardous, the district attorney

uncomfortable, smiling for the camera,

bargain-basement shoes saying that thirty-six

keep women in place. sex crimes per year is

a manageable number.

The Bear Cave (a square poem of Romania)

Twenty-five years ago at Chiscau,

marble quarry workers discovered—

trapped by an earthquake in a wondrous,

enormous cave—bones of one hundred

ninety bears, Ursulus spelaeus

(now extinct). Cold rooms of cathedral

splendor now render tourists breathless

while the insistent drip of water

counts the minutes. There is no safe place.

Invite someone to someone read "The Bear Cave" aloud and, as you listen, consider the question, Can my ear hear that a nine-syllable line consists of nine syllables? I doubt that many can answer, Yes. Instead, the effect may be that the poem seems attentively organized rather than unplanned. I find a guarded, measured quality in the uniform structure of the square poem: these are not simply words but carefully arranged thoughts--very different from the fragile imagistic Haiku--and here are two from Basho (

The hollyhocks They don’t live long

lean toward the sun but you’d never know it--

in the May rain the cicada's cry.

Discussion of syllabic verse could not be complete without mention of the fine American poet Marianne Moore (1887-1972). Born in

The Icosasphere by Marianne Moore (Syllable counts are given at the end of each line.)

"In Buckinghamshire hedgerows ( 7)

the birds nesting in the merged green density, (11)

weave little bits of string and moths and feathers and thistledown, (15)

in parabolic concentric curves" and, (10)

working for concavity, leave spherical feats of rare efficiency; (18)

whereas through lack of integration, ( 9)

avid for someone's fortune, ( 7)

three were slain and ten committed perjury, (11)

six died, two killed themselves, and two paid fines for risks they'd run. (14)

But then there is the icosasphere ( 9)

in which at last we have steel-cutting at its summit of economy, (18)

since twenty triangles conjoined, can wrap one (11)

ball or double-rounded shell ( 7)

with almost no waste, so geometrically (12)

neat, it's an icosahedron. Would the engineers making one, (16)

or Mr. J. O. Jackson tell us ( 9)

how the Egyptians could have set up seventy-eight-foot solid granite vertically? (21)

We should like to know how that was done. ( 9)

3.1.1 The complete text of the poems sampled above in Section 1 may be found in these collections.

"Geometry" by Rita Dove, from Selected Poems, Vintage Books,

"Figures of Thought" by Howard Nemerov, from The Western Approaches,

"Six Significant Landscapes" by Wallace Stevens, from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens, Vintage Books,

"Pi" by Wislawa Szymborska, translated by Stanislaw Baränszak and Clare Cavanagh, from View With a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems,

3.1.2 The four poems listed in 3.1.1 also are included in NUMBERS AND FACES: A Collection of Poems with Mathematical Imagery, published June 2001 by the Humanistic Mathematics Network.

These poems are included in the collection: How I Won the Raffle by Dannie Abse, My Number by Sandra Alcosser, Reservation Mathematics by Sherman Alexie, Numbers and Faces by W. H. Auden, Thirty-six Poets and Fibonacci by Judith Baumel, The Inclined Plane by Nina Cassian, Numbers by Mary Cornish, Geometry by Rita Dove, The Parallel Syndrome, The Fraction Line, and Brief Reflections on Logic by Miroslav Holub, To Myself by Abba Kovner, Suicide by Federico Garcia Lorca, Figures of Thought by Howard Nemerov, Ode to the Numbers by Pablo Neruda, The One Girl at the Boys’ Party by Sharon Olds, Algebra by Linda Pastan, Arithmetic by Carl Sandburg, Six Significant Landscapes (III, VI) by Wallace Stevens, A Large Number, Pi, and A Word on Statistics by Wislawa Szymborska, The Calculation by David Wagoner.

Against Infinity: An Anthology of Contemporary Mathematical Poetry, edited by Ernest Robson and Jet Wimp, Primary Press, Parker Ford, PA 1979.

Imagination’s Other Place: Poems of Science and Mathematics, compiled by Helen Plotz, Thomas Y. Crowell, NY, 1955.

My Dance is Mathematics, poems by JoAnne Growney, available Spring 2006 from Paper Kite Press, Wilkes-Barre, PA

A small online anthology is maintained by Katherine Stange, a mathematics doctoral student at

A project now in the editing stage is the publication of a collection of mathematical love poems gathered by Sarah Glaz (Department of Mathematics,

Return to Outline Top of page

3.2.1 Lewis Carroll's mouse tale is from Chapter 3 of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, available online through the Classical Library website. A Google-search using either “concrete poetry” or “visual poetry” leads to a number of interesting examples. One engaging site is maintained by Michael P. Garofalo. This example from Garofalo’s site illustrates the use of idea and image instead of meter and rhyme in concrete poetry.

3.2.2 One of the best known of the early "visual" poets was the French experimental poet, Guillaume Apollonaire, who wrote a number of poems in diagrammatic form that he called "Calligrammes."

3.2.3 For a given line of verse, readers do not necessarily all agree which syllables will be stressed, For example, for the line

a reader might choose not to stress the initial word--instead stressing the first syllable of "E-ven."

3.2.4 UbuWeb, a website used above for Apollonaire's "Heart, Crown, and Mirror" also contains Henry Lok’s square poem. A text interpretation of the manuscript photo appears on page 166 of Thomas P. Roche, Jr.'s Petrarch and the English Sonnet Sequences (New York: AMS Press, 1989). Roche's Appendix G goes on to point out the complexity of the structure within the square. For example, the first and final "pillars" give a two-line verse:

God makes kings rule for heaue[n]s; your state hold blest

And still stand will their shields; fear yields best rest. [Roche, 550]

Embedded in the poem also are other poems, found by tracing the patterns of sub-squares or crosses.

Return to Outline Top of page

Return to Outline Top of page

There are a myriad of combinatorial questions that maybe posed about poetry--question such as, For a Shakespearean sonnet, how many ways are there of arranging the sonnet's lines so that the rhyme scheme is preserved? Although the problem might be fun to solve, the answer is of little interest--and more interesting result, how many of these make sense? cannot be computed.

Of interest, however, is that the Catalan and Bell numbers are involved when we count rhyme schemes. For a stanza of n lines, the number of possible rhyme schemes is given by the nth

They say who play at blindman's bluff

and strive to fathom space

That a straight line drawn long enough

Regains its stating place.

Martin Gardner has written extensive and readable introductions to the Catalan and

Return to Outline Top of page

This is a bigger world than it was once

it expands an explosion it can't help it it has

nothing to do with us with whether we know or

not whether our theories can be proved

whether or not a mathematician

knew a better class of circles

(he has a name, Taniyama, a Conjecture)

than was ever known before before—

not circles, elliptic curves. Not doughnuts.

Not anything that is nearly, only is, such

a world is hard to imagine, harder to live in,

harder still to leave. A little like love, Dear.

I have been working with Sarah Glaz, a mathematician at the University of Connecticut, to gather and edit a collection of mathematical love poems and this effort has led, for example, to Ramke’s poem above and to "Geometry" by X. J. Kennedy--and also to a fine book, alphabet, by Inger Christensen, and translated from Danish by Susanna Nied. alphabet is structurally based on the Fibonacci sequence--after a one-line title and a one-line stanza are stanzas of two lines, then three, then five and eight. Eventual stanzas explore the sequence in different ways and the impact of the structure is strong and surprising.

There is no way to end a consideration of the links between mathematics and poetry. They go on and on. But I stop here and invite you to contact me with your ideas and comments.

Return to Outline Top of page JoAnne Growney's HOME page